Arriving in Salento, which sits in the heart of Colombia’s ‘eje cafetero’ (or coffeelands) in the late afternoon sunshine is a truly colourful joy. The hotels, cafes and bars surrounding the town’s main square are painted bright and happy shades of red, yellow, blue and green. Instead of the yellow city taxis, a line of Jeeps and Willys are ready to ferry us up the hill to La Serrana, a dairy farm and hostel with wonderful views of the green, coffee tree laden hills all around.

The next day we pile into another Willy, the guys are all loitering and vying to be the last in line so they get to stand on the back footplate in manly fashion, as we bump along gravelly roads into the lush verdant Valle del Cocora. After heavy rains, the path up the valley is a fun obstacle course of mud, logs and creaking wooden swing bridges, and the climb all the way up to the Finca Acaime is well worth it for the pleasure of watching hummingbirds flitting in and out of the trees and the bird feeders as we sip our drinks!

Back down the hill and then up another steep hillside takes us to our first views of the famous tall wax palms of the Valle del Cocora. Clouds are now swirling up the valley giving these lofty slender trees an almost ethereal appearance.

Back in Salento, the bustling little town has plenty to offer for hungry walkers – and the peanut butter chocolate brownie at the Brunch café is heaven for any chocoholic – rich, gooey, nutty, and so enormous it takes some willpower to eat it all. But I just about force it down!

It was in Salento too that I got on a horse for about the third time in my life, under the charming guidance of Señor Delio, who was the embodiment of chivalry. My horse, a grey called Muñeco (puppet), insisted on being in the lead the whole way through the town, along a narrow ridge, down a zigzagging tiny track so steep we had to almost stand in the stirrups so as not to go over the horse’s head! Crossing the first river was also a nail biter for this amateur rider as Muñeco carefully picked his way into the belly-deep current and scrambled to the other bank – the next two shallower rivers were tame by comparison! We trotted and splashed through streams, muddy fields to a pretty waterfall. The heavens opened on the way back, but Señor Delio had us covered with huge thick plastic ponchos.

If you ever come to Colombia, an absolute must is to have a go at playing Tejo! Think ten pin bowling, except instead of pins you have a small circle of tiny gunpowder sachets resting on an old horse shoe set in a big clay frame, and instead of bowling a ball, you throw a big heavy stone and see if you can explode something! Three points for a direct hit, six if your stone ends in the middle of the circle, and nine if you achieve both! Throw in a few rounds of beer, a bottle or five of aguardiente (Colombian firewater, tastes a bit like anis), and you’ve got yourself a pretty hilarious and explosive night!

As Salento is in the heart of the coffee region, there are plenty of farms you can visit. As there weren’t any Fairtrade groups nearby, I eschewed the offer of a visit to El Ocaso, a large and very professional looking coffee plantation with multiple other certifications and tours from guides in neat branded red tour guide jackets, and instead headed to Don Elías’ small organic family farm down the road, where his son Jonh (no, that’s not a spelling mistake!) took us round in his farm clothes and mud spattered boots. Here the several varieties of coffee are interspersed with banana and plantain palms, avocado trees, pineapples, guava, yucca, naranjilla, and lots of flowers, all contributing to the organic and diverse farming methods they practise here. Taking us around his 4 hectare farm, Jonh told that in a good year they can produce up to 8 or 9 tonnes of coffee beans, but last year only yielded between 4 and 5. The family only has two routes to market: direct sales to visitors to the farm and the “Comite de los cafecultores” or farmers’ association where the prices for their parchment coffee (fermented, dried beans before the papery outer shell is removed) have recently been falling. It was a reminder of how valuable the role of a decent, democratic farmer cooperative can be, and access to a fair market with transparent pricing. Back at the house, we grind some recently roasted beans and Don Elias’ wife, Jonh’s mother brews up the strongest, best espresso I’ve had in Colombia. I don’t hesitate to purchase a bag of their delicious beans, now nestling along with the Ecuadorean chocolate in my increasingly straining-at-the-seams backpack.

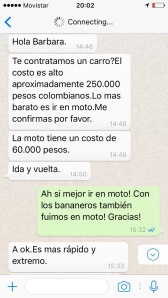

I’ve been travelling from Popayan to Cali and Salento with Ben and Olivia from Washington DC, who have also quit their jobs working for a US Senator and as ICU nurse respectively to travel (check out their fab slackerbackpackers Instagram feed here). Now the three of us embark together on the road from Salento to Jardín, involving first a local bus along beautiful valleys to Pereira, then a big bus heading for Medellín which sets us down at the town of La Pintada. Here, we are informed that there are no more buses today going where we want and we need to take a ‘colectivo’ or shared taxi – in this case a mototaxi! After a bit of haggling, we squash all our big rucksacks in, and squeeze the three of us in on top, and set off along shady green roads for the hour’s ride to the town of Bolombolo – with this motorised tricycle all piled up with luggage and Ben in his Panama hat we feel like a proper world traveller cliché as we roar along with the wind whipping in our faces. At Bolombolo, we tumble out of the mototaxi to sit under a shelter and a large tree at a crossroads, waiting for our final bus to pass for another hour. Just as the sun is going down and the mosquitoes are starting to bite, one finally comes and we grab the last three seats. All in all, the journey takes us 9 hours!

I’m almost reluctant to include Jardín in this blog, because it’s one of those true charmingly hidden gems and a slice of Colombian life you don’t want everyone to know about in case it gets become spoiled by tourism! It’s dark when we arrive, but the town square is alive with food stalls, bars, music playing and people sitting around the brightly painted wood-clad houses with beers, coffees, rum and aguardiente. There is a relaxed sense of pride in this place, reflected in the spotlessly clean streets and multicoloured paint, decorations and flowers of the houses that just makes you want to smile. People here both work hard and play hard. At 5.30 am the streets are already busy with people heading off to farms and construction site in their wellies, opening up the cafés for the morning ‘tinto’ (sweet black coffee shot) or climbing into buses to nearby towns, or washing their doorsteps. You can take tiny cage like cable cars to lift you over the river and up the hills surrounding this town nestling in the valley, and there are plenty of offers of horse rides to local waterfalls, although the most famous cascade in a cave is closed off due to recent landslides. Towards late afternoon, as the sun is going down, groups of men in crisp shirts and wide brimmed hats, and women in equally pristine outfits, gather in the painted seats around the colourful edges of the main square, watching the world go by, sharing the day’s news over afternoon tea or fresh juices, as the ‘carritos’ set up stall selling chicken, pork and a wide selection of deep fried empanadas and sweet pastries. It’s at this time that horses start appearing in the streets of the squares, prancing past in a bouncing trot, their riders practising for monthly local competitions.

Here’s a little clip of what happens if you just sit around people watching…

For birdwatchers, Jardín contains one final big treat. Down by the river, and in the gardens of a local house, around 15-20 “gallitos del roca” come to lek every morning and afternoon These bright red and extraordinarily crested male birds announce their appearance with a grating screech, and proceed to bow, bob and flap at each other in a show of macho pride they hope will win them the attention of the rather more discreetly plumaged female (I briefly spot one lurking across the river discreetly checking out the action). They’re like a little wonder of the world in their own right. I’ve posted a little video clip for you to enjoy here!

I’ve already stayed a day longer in Jardín than planned, and I’m truly sad to leave it. With Salento, it’s definitely one of my favourite highlights of Colombia to date. But the bright lights of Medellín are beckoning … and I’m eager to see the famous transformation of this city, once dubbed the most dangerous in the world. I’ll tell you all about it in my next blog!