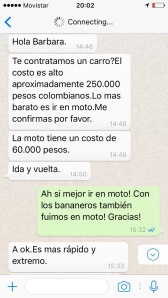

The warning signs were all there. I was WhatsApping with José Diaz of Fairtrade coffee cooperative Cooagronevada about visiting some of their members in Colombia’s Sierra Nevada, when he asked me if I’d prefer to go by car or motorbike. Having trundled around the banana farms on the back of Foncho’s motorbike for the previous few days, I was feeling cocky. And noting the large price difference, I didn’t hesitate. “Better to go by bike,” I replied. “Ah yes,” responded José, “it’s faster and more extreme.”

More extreme? It doesn’t take long for me to work out what he meant. I am met in Minca by Cooagronevada members Elias Flores and Julio Vega. Julio also works for the cooperative on technical standards compliance. He hands me a helmet, and we’re off up the mountain. Holding on to the back of his motorbike for dear life as we leave the paved road and hit stony gravel, swerve around several recent land slips, and churn through mud from recent rain, it feels at times more like a motocross circuit than a road. Julio steers expertly around the obstacles, but twice I lose my nerve and get off to walk around the impending mud bath, leaving him to skid and splatter including around a large truck that is stuck in the mud.

After just over an hour, we descend into a valley, cross a bridge over the Toribio river and pull in next to a shelter where local coffee farmer Genry San Juan is doing a bit of motorbike maintenance. I’m not surprised, these roads must take their toll on any vehicle. “That’s a pretty bad road,” I say, conversationally. “Oh, the road is really good right now,” comes Julio’s reply, “You should see it during the rainy season.”

This is the valley of Central Córdoba, where seventeen of Cooagronevada’s 72 members live scattered up the mountainsides. To reach the farms from here, there are only two ways to go, either on foot or by mule/horse. We set off in the heat, climbing the twisting narrow paths that snake up the hillside. Fifteen minutes later we reach the homestead of Julio San Juan, his wife Consuela, son Andres and daughter Laura, who have three farm plots between them. As we climb up to the house, I’m shown large black plastic bins sunk in a line down the slope. With support from the ethical lender Rabobank, these are collecting the ‘aguas mieles’, the run off liquid from the depulping of coffee cherries, which left untreated can contaminate water supplies, but instead is now being filtered and recycled as a natural fertiliser. It’s all part of their organic and sustainability commitment. Julio also proudly shows me his new ‘silo’ or coffee drying machine, bought with money from the same project, which supplied nineteen such machines to different members (this machine is serving all three family coop members). This helps the family to achieve efficient drying of their beans even during rainy weather, when natural drying on racks can take weeks and affect the final quality of the beans. It’s all part of a quality improvement process.

In the last couple of years, with the support of Fairtrade premiums, the family have also made renovations to their house, which now has a new corrugated roof, a refurbished outdoor terrace, and also new tiled coffee washing station. With flowery hanging baskets and a wonderful view down the valley, it’s a home and a farm to be proud of, and a far cry from the dilapidated rough adobe houses we’ve passed on the way here.

The same story is repeated again and again as we climb higher and higher and move from one house to another. With the money they are earning now through the Coop, family after family have dramatically improved their living conditions, with new roofs and newly painted or plastered walls, proper bathrooms, and pretty shiny tiled verandas. They’ve also transformed their ability to process their own coffee with brand new covered ‘marquesinas’ or sun-based drying racks, improved coffee washing facilities with clean while tiled basins and water channels, depulping machines, organic fertiliser storage areas and ‘aguas mieles’ systems. The coffee drying racks are pretty handy for drying your clothes in these out-of-harvest season rainy days too! In every home there are signs of further refurbishments going on. These farmers are on a mission!

At the third house we visit, I ask mother-of-three and President of the cooperstive’s women’s committee, Nayibe San Juan Barbosa what has changed as a result of being part of a cooperative selling on Fairtrade terms. “Look around you,” she replies, “everything you see – it has all changed! We’ve renovated the whole house, the roof. We now have tiles on this patio, it was just an earth floor before.” Her grown up oldest son arrives for lunch, he’s been busy pruning coffee bushes to improve their productivity, and the family has also got a nursery of new coffee plants. On this sunny day, looking at the wonderful views around, I have a strong sense of how these farmers through their own endeavours are overcoming the geographical and economic barriers that held them in poverty for so long. But life is still far from perfect. “What we really need now here is a phone signal,” says Nayibe. “That is the thing that is keeping us isolated now.”

They do have a TV signal, however. At the last, and highest, farm we visit, Genry San Juan has finished working on his motorbike and come home. Members of the family are watching the Champions League final between Juventus and Real Madrid. Tension here in Colombia is high – will Colombia’s national squad member James (pronounced Ha-mez) come off the bench for Real or not? Genry’s ten year old daughter Angelica is not too bothered about the football, so I leave the TV watchers and ask her where she goes to school. There’s no secondary school anywhere near here, and she, like most other children when they reach ten years of age, is now going to a weekly boarding school in the town. She tells me she loves it, and rattles off a whole series of phrases she’s learned in English. Genry points at a hill in the distance – the primary school Angelica used to attend is somewhere in the valley that lies beyond it. There were days she would leave home at 6.30am and not get to school until 9, her father says. I’m not surprised she loves not having to do that arduous walk on steep hillsides each day anymore. Right now, however there’s no school at all for Angelica to go to, as public sector teachers across the whole of Colombia have been on strike for several weeks in protest at poor pay levels and lack of school funding, with overcrowded class sizes. Only the private schools are operating, and their expensive fees are still out of reach for a typical small scale farming family here. Likewise, there’s no health clinic in the area, so if you get sick, it’s a rough trek down to Minca or another town to see the doctor. Life in these mountains is still pretty isolated.

Genry tells me he managed to produce 8,300 kilogrammes of coffee from his 8 hectares of coffee last season, but more than that, he now knows the “Taza” or cupping quality score of his coffee. Previously the farmers would manage quality control through mostly visual clues – the colour of the cherries, the quality of the bean through the fermentation, washing and drying stages, and these are all still important factors. However, with money from Fairtrade premiums and technical support from their US-based export partner Sustainable Harvest, the cooperative has now installed a full cupping lab, and all farmers have been attending workshops to learn about coffee taste profiling. “Before joining the cooperative, we used to just harvest our coffee and deliver it to the market,” says Genry. “Now we are taking pride in the quality of our coffee, we understand much more about how important the right times for fermentation and drying are, and how to improve our production. This gives me hope for the future.” We’re interrupted by a massive cheer from the football watchers – Juventus have equalised with a brilliant overhead kick. But poor old James never gets onto the pitch in Real Madrid’s eventual championship win.

A couple of days later, back in Santa Marta, I drop into Cooagronevada, where the coop’s energetic manager Sandra Palacios proudly show me all the new equipment they’ve bought with Fairtrade premiums. A massive coffee dryer for the farmers who don’t yet have their own silo, shiny roasting machines, a coffee mill, and a coffee tasting set they use for training members and regular cupping. On the shelves, samples of washed green beans from members are bagged and labelled. When farmers deliver their coffee to the coop, samples are taken, roasted and tasted. Their trained cupper and the farmer taste together and discuss the details of how that farmer fermented, washed and dried his or her beans, in a constant learning process.

The new quality control system seems to be working well, as the latest harvest has managed to surpass the magical 84 points on the ‘taza’ tasting scale that is the indicator for great quality, giving them a coffee that roasters would fight over. Sandra, who was one of the founding farmer members of the Coop before becoming its manager, says that having both the Fairtrade certification and great quality coffee gives them a real advantage in the negotiation. “All of our members’ coffee is certified organic and Fairtrade,” she says. “So if anyone wants to buy it, that’s our minimum deal – the Fairtrade price, plus the organic supplement and the Fairtrade premium. Even if they don’t want to label their own final brand coffee as Fairtrade, they still have to buy it from me on these terms. That’s the deal.” Now the cooperative is going further, and is separating the beans from its 26 women members to be able to offer a “grown by women” coffee, and has become the first cooperative in Colombia to carry a ‘Women Care Certified’ logo started by the Costa Rican Alliance for Women in Coffee. In an even more daring move during the last harvest, the cooperative also segregated the beans harvested in the three days before and after the full moon. The resulting coffee notched up 85.5 points on the coffee taste scale, including berry fruit notes that made it quite sought after. Whether it was the lunar influence or the overall emphasis on quality control hardly matters as Sandra beams with pride as she tells me about it. And when some fresh brewed espressos arrive for us, I am blown away by its flavour. It’s easily the best coffee I’ve tasted in 2017, with a superb balance of chocolate-caramel and hint of blackberry that leaves a pleasingly rounded taste in your mouth. Who knew? Full Moon coffee, folks, you heard it here first!

The cooperative is now roasting and packing its own Café Pasión brand, with the aim of tapping into Colombia’s fast growing tourist industry and changing café culture. It’s just 10 years since Cooagronevada was founded in 2007, and just six years since achieving FLOCERT certification in 2011, and they’ve already come a tremendous long way through their members’ own determined leadership, bold vision, along with Sandra’s refusal to take any bullshit from her buyers. Now she has an increasingly excellent quality product to offer. So, where next? Could there be a day when every individual small farmer could market their own single estate quality product, complete with cupping profile? Sandra thinks with modern technology and their increasing ability to manage microlots of coffee, that day may not be too far away. Beyond this, the cooperative is only exporting to the United States, through partner Sustainable Harvest to brands such as Lohas Beans and Café Moto, and has not yet managed to break into the European market.

Being purely selfish, and knowing the one bag of coffee now squashed in my rucksack isn’t going to last long at all, I would love to see a dedicated UK Fairtrade importer-roaster such as Cafédirect, TWIN, Cafeology or Matthew Algie get their mitts on a container or two of their coffee. Because this is not just great coffee, it is genuinely transforming the living and working conditions for the families I met – no longer are they just growers of an average raw commodity, they are now active and knowledgeable protagonists in the specialty coffee market. And for a bunch of remote scattered farming families high in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, that leaves a very satisfying taste in your mouth!

Being purely selfish, and knowing the one bag of coffee now squashed in my rucksack isn’t going to last long at all, I would love to see a dedicated UK Fairtrade importer-roaster such as Cafédirect, TWIN, Cafeology or Matthew Algie get their mitts on a container or two of their coffee. Because this is not just great coffee, it is genuinely transforming the living and working conditions for the families I met – no longer are they just growers of an average raw commodity, they are now active and knowledgeable protagonists in the specialty coffee market. And for a bunch of remote scattered farming families high in the mountains of the Sierra Nevada, that leaves a very satisfying taste in your mouth!

To find out more about Cooagronevada’s coffee, click here. My thanks to Sandra Palacios, Juan Francisco Dìaz Rocca, Julio Vega, Elias Flores and all the farmers and families of Cooagronevada I met for their wonderful hospitality.

Cooagronevada have just released their newly branded Women’s Coffee – take a look and follow their news on Facebook https://www.facebook.com/cooagronevada/posts/1339334706119565

LikeLike